The 1001 Nights

The One Thousand and One Nights (or the ARABIAN NIGHTS’ ENTERTAINMENTS), a collection of Oriental tales, first made known to Europe by Antony Galland, a French orientalist, under the title of The Thousand and One Nights, Arabian Stories, Translated into French. They were published at Paris, in 12 volumes, from 1704 till 1717, and were received by many as the production of the genius of the translator himself, rather than the collection of an unknown Arabian author, as Galland had stated in his dedication.

Oriental scholars did not hesitate at first to declare against their authenticity, and denounce them as forgeries. Having taken only an obscure place in the literature of the east, and their style unfitting them from being classed among models of eloquence or taste—having no object of a religious, moral, or philosophical kind in view, while the manners and customs delineated in them were different from all stereotypical ideas of those of the Middle East — their success took the critics by surprise. The work became highly esteemed by the public; it filled Europe with its fame; it had abundance of readers, and no lack of editors.

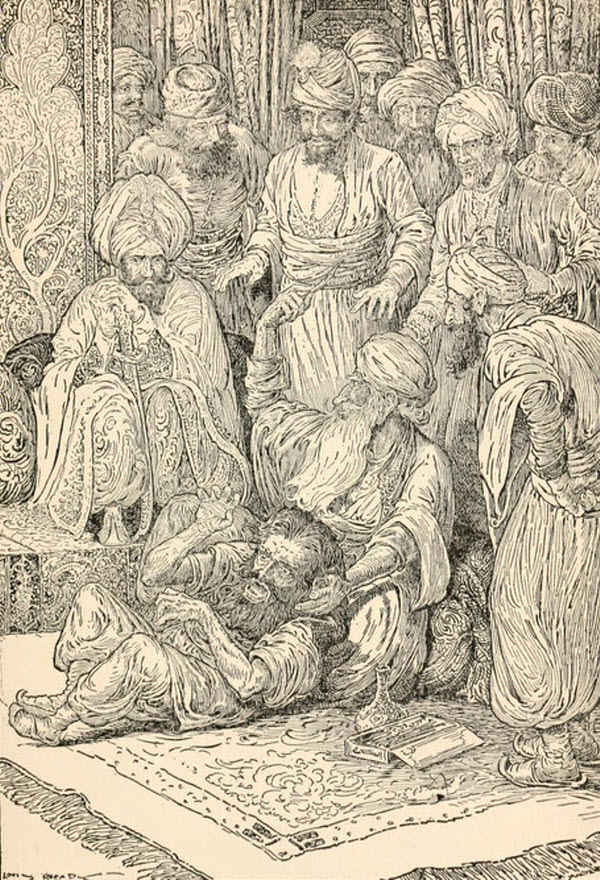

Few books have been translated into so many different languages, and given delight to so large a number of readers. It may be said that, in these Oriental tales, there has sprung up a new branch of literature, for their influence on the literature of the present day is easily discernible. Here are found, depicted with much simplicity and great effect, the scenes of the town-life of the Moslem. The prowess of the Arab knight, his passion for adventure, his dexterity, his love and his revenge, the craft of his wives, the cruelty of the caliphs, are all dramatically delineated—far more vividly represented, in fact, than is possible in a book of travels; while gilded palaces, charming women, lovely gardens, and exquisite repasts captivate the senses of the reader, and transport him to the land of wonder and enjoyment. Besides entertaining the mind with the kaleidoscopic wonders of a teeming and luxurious fancy, which is their most obvious merit, they present a treasure of instruction upon life in general, and oriental life in particular. And this is undeniable, notwithstanding the fact, that the aspects of society they depict are far from standing high in the social scale, either as to civilization or morality. Indeed, the first translator, having a conviction of a demoralizing tendency of this kind, avoided giving several objectionable parts of some of the stories. The thread of the narrative in these entertainments is generally simple and clear, often leading into the departments of fable, and occasionally into the regions of the supernatural and the domains of popular superstition. The tales, even when long, are not tiresome; for they consist of shorter stories branching off from the main one, or rather encased within it, the smaller within the larger, and perhaps a smaller within that, like the little boxes used by magicians.

A more thorough acquaintance with medieval Arab life has proven the genuineness of the stories, and the truthfulness of their general representation of the mind of the Moslem. In them there are evident signs of a declension from a refined and superior civilization; the marvelous and supernatural is predominant; despotism in all its forms is manifest; and a prevalent falsity and insincerity of character visible, not only in the narrative, but in the tone of common conversation, replete as it is with oaths and asseverations.

For many years all doubt as to the authenticity of the Thousand and One Nights has been dispelled. Several manuscript copies have been found, and no less than four editions of the Arabic text have been published. The origin of the work — where and by whom written — is still involved in mystery. According to some, the tales are susceptible of a threefold division. The most beautiful, and in fancy the richest, appear to have come from India, the cradle of story and fable; the tender and often sentimental love tales seem of Persian origin; while the masterly pictures of life, and the witty anecdotes, claim to be the product of Arabia. The baron de Sacy, in 1829, thus stated his opinion on these points. Speaking of the work he says; “It appears to me that it was originally written in Syria, and in the vulgar dialect; that it was never completed by its author; that, subsequently, imitators endeavored to perfect the work, either by the insertion of novels already known, but which formed no part of the original collection, or by composing some themselves, with more or less talent, whence arise the great variations observable among the different manuscripts of the collection; that the inserted tales were added at different periods, and perhaps in different countries, but chiefly in Egypt; and, lastly the only thing which can be affirmed, with much appearance of probability, in regard to the time when the work was composed, is—that it is not very old, as its language proves, but still that, when it was brought out, the use of tobacco and coffee was unknown, since no mention of either is made in the work.”

Galland’s French edition was speedily translated into all the languages of Europe; edition following edition with great rapidity, some of them with enlargements and others with modifications. Latterly, a Dr. Scott gave a superior English edition, “carefully revised, and occasionally corrected from the Arabic.” At length a new English translation from the Arabic, with copious notes and highly artistic embellishments, appeared in 1839. It was the work of Edward William Lane, a gentleman whose long residence in Egypt enabled him to acquire so thorough a knowledge of the language, manners, and customs of the Egyptian Arabs, as has furnished not only a superior version, but a series of notes embodying a portraiture of Egypto-Arabian life at once faithful and vivid. See Kirby’s translation, and the Villon society edition (1882-84).

The popularity of this wonderful book has given rise to hundreds of imitations. Among the best of the French are — Les Mille et Un Jours, Mille et Une Quart d'Heures. The best English translation is by noted Victorian era explorer and Orientalist, Richard Burton, who produced an uncensored version of the Arabian Nights.

This article was adapted slightly from the article on the 1001 Nights (Arabian Nights) published in the Universal Cyclopedia, 1890 Edition.

Sinbad the Sailor

Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp

Arabian Nights: The History of the Fisherman